In 2019 researchers from Security Without Borders discovered the Exodus malware had infected almost 25 apps in the Google Play Store (Franceschi-Bicchierai, 2019), further investigation revealing that it was developed by eServ and authorised by Italian law enforcement (Gallagher, 2020). Due to malfunctioning target validation, it infected and exfiltrated data from non-target devices.

Christen et al (2020) identifies a number of tensions between security and ethical issues which I believe are appropriate:

- Between security and individual privacy. To achieve its goals for security, Exodus collected a variety of data including: recordings of surroundings and calls; chat apps; gps data; calendars; email and browsing history (Security Without Borders, 2019). This infringed on the rights to privacy, autonomy, ownership of devices and data of Italian citizens. Initially this may seem a case of Kidder’s (1996) individual vs community. Realisation of the failure to validate targets – as required by Italian Law (Franceschi-Bicchierai, 2019) – makes this seem more likely an error. But with eServ employees reportedly “playing back phone conversations of secretly recorded calls aloud in the office” (Gallagher, 2020) – a further breach of privacy and confidentiality in itself – it seems more likely a moral wrong and displays flagrant disregard for the rights of the victims and of any ethical considerations.

- Between national/state and individual security. Exodus opened an unencrypted port on infected devices, thus creating a vulnerability. Again infringing on the rights to privacy, autonomy, ownership of devices and data. The harm principle (The Ethics Centre, 2016) may not have been breached, but Exodus certainly facilitated the potential for harm by making it possible for criminals to take control of a device via a backdoor (Greenberg, 2017).

- Between security and discrimination. Although an iOS version of Exodus was discovered (Newman, 2019), the most intrusive and prevalent form was on Android. Christen et al. (2020) claims this is targeting and profiling people of a lower socioeconomic status, potentially violating the human right of discrimination (Yaghmaei et al., 2017 via Christen et al., 2020, p. 77).

A initial response may be to say that a balance between security and ethical considerations could be achieved by ensuring that the target validation was functional. If this is rectified, then Exodus could be a powerful tool for law enforcement while preserving the rights of the general public. But the aforementioned poorly managed tensions and lack of respect by eServ for exfiltrated data, demonstrates that the unethical conduct ran deeper than the malfunctioning target validation. These issues combined with the press coverage of the situation would make it difficult for balance to be reached in the application of Exodus and I think it would benefit from termination and a fresh start with ethical considerations baked into the planning process.

Upon recent reflection – of this case, Stuxnet, the security of IoT devices and the ethics of deploying cyber weapons more broadly – I think that Exodus could have been developed and tested in an ethical manner and that this could also have been extended to its deployment and operation.

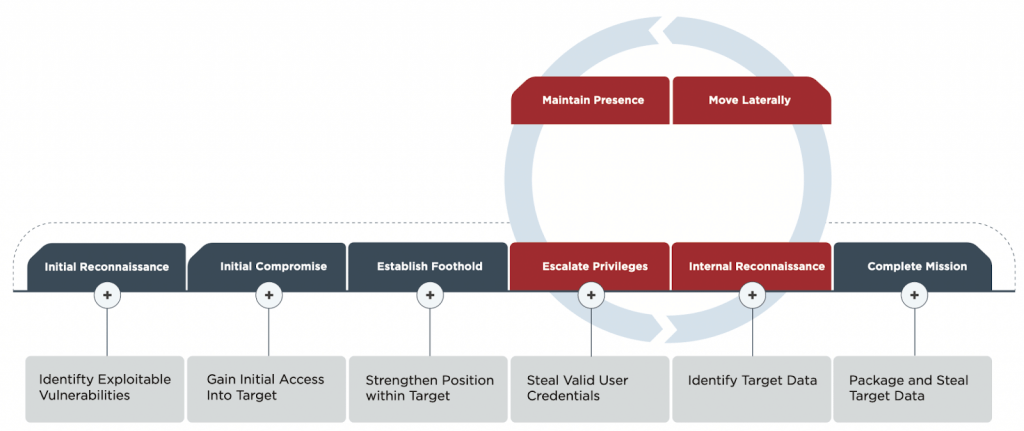

When we are defending we are encouraged to adopt an attacker’s mindset as a way of identifying vulnerabilities and attack vectors. I propose that when attacking – with Exodus being an attack – we adopt a defender’s mindset with a view to identify and reduce collateral damage that may occur. The cyber kill chain (CKC) is a tool that can be used by defenders to prepare for attacks. We could use the CKC to help us to pause and consider the implications of our attack at each of its phases – taking the opportunity to embed ethical considerations as we do so.

Examples of high level considerations include: do validated targets and non-targets have different branches in the CKC? Which phase do we draw the line on proceeding if we are unable to validate a target? As we proceed through the CKC, questions such as: Is this a target? What data are we collecting? How is the data protected? Could data leakage cause harm? What is the data’s pathway to destruction? Are we infringing on rights? Whose rights? Why are we infringing on these rights? Should we be?

Looking specifically at the FireEye attack lifecycle, above, we could ask these questions at each stage of the attack to help embed ethical thinking into deployment of a cyber weapon.

| Attack phase | How we can consider/balance ethical implication |

| Initial reconnaissance | What are we doing with non-mission related the data we collect? Is it PII or prone to inference attacks? Are we destroying it? If not, how are we keeping it secure? |

| Initial compromise | Can we target the attack? If it is spread in a virus-like manner, can we limit its leakage (e.g. Stuxnet limited the number of times an infected device could spread the worm). The more we can target the attack, the less consideration we need to give to non intended targets. |

| Establish foothold | Can we identify whether or not this is a valuable target? Yes: continue the attack. No: stop attack. |

| Escalate privileges | What are the minimum privileges we need to determine whether this is a valid target? Can we identify whether or not this is a valuable target? Yes: continue the attack. No: stop attack. |

| Internal reconnaissance | How can we determine if this is a valid target? Undertake the minimum internal recon to establish this. Can we identify whether or not this is a valuable target? Yes: continue the attack. No: stop attack. |

| Move laterally | This phase is likely to only affect non-targets if the target is in a large organisation, eg a particular person in a company or organisation. As we move laterally and leave the current device, we need to consider what we do with any data we have collected. Is it PII or prone to inference attacks? Is it proprietary or IP? Are we destroying it? If not, why not and how are we keeping it secure? |

| Maintain presence | When we reach this stage we need to have confirmed that we have a valid target. To maintain a presence in a non-valid target would be breaching their privacy, ownership of their device and data and potentially their security. |

| Complete mission | This depends on our ability to identify the valid target. If we have a valid target we can execute our mission. If we do not, we cancel the mission, this should consider aspects such as: what we do with any data we have exfiltrated, how do we respect their privacy? Encrypting the data? Destroying it? System clean up, removing the weapon from the non-target’s system. This will help to hide our mission but also return autonomy and ownership to the individual.Disclosure after the mission: notify the public of the mission, what was achieved and the measures taken to ensure that non-targets were respected and protected from the weapon. |

By considering the ethical implications at each phase of the attack lifecycle, we are embedding it into the design, deployment and operations. I believe applying such an approach in Exodus would have led to a more considered approach and helped to reduce collateral damage and provided an ethically defensible position when things went wrong.

References

Casal Moore, N. (2017, May 1). Smartphone security hole: “Open port” backdoors are widespread. University of Michigan News. https://news.umich.edu/smartphone-security-hole-open-port-backdoors-are-widespread/

Christen, M., Gordijn, B., & Loi, M. (2020). The ethics of cybersecurity. Springer Nature.

Cohen, D. of G. P. in P. E. S., & Cohen, S. (2004). The nature of moral reasoning: The framework and activities of ethical deliberation, argument, and decision-making. Oxford University Press, USA.

FireEye Inc. (2019). Red Team Operations Data Sheet. FireEye. https://www.fireeye.com/content/dam/fireeye-www/services/pdfs/pf/ms/ds-red-team-operations.pdf

Franceschi-Bicchierai, L. (2019, March 29). Researchers find google play store apps were actually government malware. https://www.vice.com/en/article/43z93g/hackers-hid-android-malware-in-google-play-store-exodus-esurv

Gallagher, R. (2020, January 16). The Crime-Fighting App That Caused a Phone-Hacking Scandal in Italy. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-01-16/the-crime-fighting-app-whose-developers-allegedly-went-rogue

Greenberg, A. (2017, April 28). An obscure app flaw creates backdoors in millions of smartphones. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/2017/04/obscure-app-flaw-creates-backdoors-millions-smartphones/

Kidder, R. M. (1996). How good people make tough choices: Resolving the dilemmas of ethical living. Touchstone.

Newman, L. H. (2019, April 8). “Exodus” Spyware Posed as a Legit iOS App. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/story/exodus-spyware-ios/

Security Without Borders. (2019, March 29). Security Without Borders. Security Without Borders. https://securitywithoutborders.org/blog/2019/03/29/exodus.html

The Ethics Centre. (2016, October 27). What is The Harm Principle? Ethics Explainer by The Ethics Centre. The Ethics Centre. https://ethics.org.au/ethics-explainer-the-harm-principle/

Yaghmaei, E., van de Poel, I., Christen, M., Gordijn, B., Kleine, N., Loi, M., Morgan, G., & Weber, K. (2017). Canvas white paper 1 cybersecurity and ethics. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3091909